Although many events in the Bible are very familiar in the West even to non-religious people, the overall narrative is much less well known. I reproduce below the synopsis from Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman’s fascinating book, The Bible Unearthed.

The heart of the Hebrew Bible is an epic story that describes the rise of the

people of Israel and their continuing relationship with God. Unlike other

ancient Near Eastern mythologies, such as the Egyptian tales of Osiris, Isis,

and Horus or the Mesopotamian Gilgamesh epic, the Bible is grounded firmly in

earthly history. It is a divine drama played out before the eyes of humanity.

Also unlike the histories and royal chronicles of other ancient Near Eastern

nations, it does not merely celebrate the power of tradition and ruling

dynasties. It offers a complex yet clear vision of why history has

unfolded for the people of Israel – and indeed for the entire world – in a

pattern directly connected with the demands and promises of God. The people of

Israel are the central actors in this drama. Their behaviour and their adherence

to God’s commandments determine the direction in which history will flow. It is

up to the people of Israel – and, through them, all readers of the Bible – to

determine the fate of the world.

The Bible’s tale begins in the garden of Eden and continues through the stories

of Cain and Abel and the flood of Noah, finally focusing on the fate of a single

family – that of Abraham. Abraham was chosen by God to become the father of a

great nation, and faithfully followed God’s commands. He travelled with his

family from his original home in Mesopotamia to the land of Canaan where, in the

course of a long life, he wandered as an outsider among the settled population

and, by his wife, Sarah, begot a son, Isaac, who would inherit the divine

promises first given to Abraham. It was Isaac’s son Jacob – the

third-generation patriarch – who became the father of twelve distinct tribes.

In the course of a colourful, chaotic life of wandering, raising a large family,

and establishing altars throughout the land, Jacob wrestled with an angel and

received the name Israel (meaning “He who struggled with God”), by which all his

descendants would be known. The Bible relates how Jacob’s twelve sons fought

among one another, worked together, and eventually left their homeland to seek

shelter in Egypt at the time of a great famine. And the patriarch Jacob declared

in his last will and testament that the tribe of his son Judah would rule over

them all (Genesis 49:8-10).

The great saga then moves from family drama to historical spectacle. The God of

Israel revealed his awesome power in a demonstration against the pharaoh of

Egypt, the mightiest human ruler on earth. The children of Israel had grown into

a great nation, but they were enslaved as a despised minority, building the

great monuments of the Egyptian regime. God’s intention to make himself known to

the world came through his selection of Moses as an intermediary to seek the

liberation of the Israelites so that they could begin their true destiny. And in

perhaps the most vivid sequence of events in the literature of the western

world, the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers describe how through signs

and wonders, the God of Israel led the children of Israel out of Egypt and into

the wilderness. At Sinai, God revealed to the nation his true identity as YHWH

(the Sacred Name composed of four Hebrew letters) and gave them a code of law to

guide their lives as a community and as individuals.

The holy terms of Israel’s covenant with YHWH, written on stone tablets and

contained in the Ark of the Covenant, became their sacred battle standard as

they marched toward the promised land. In some cultures, a founding myth might

have stopped at this point – as a miraculous explanation of how the people

arose. But the Bible had centuries more of history to recount, with many

triumphs, miracles, unexpected reverses, and much collective suffering to come.

The great triumphs of the Israelite conquest of Canaan, King David’s

establishment of a great empire, and Solomon’s construction of the Jerusalem

Temple were followed by schism, repeated lapses into idolatry, and, ultimately,

exile. For the Bible describes how, soon after the death of Solomon, the ten

northern tribes, resenting their subjugation to Davidic kings in Jerusalem,

unilaterally seceded from the united monarchy, thus forcing the creation of two

rival kingdoms: the kingdom of Israel, in the north, and the kingdom of Judah,

in the south.

For the next two hundred years, the people of Israel lived in two separate

kingdoms, reportedly succumbing again and again to the lure of foreign deities.

The leaders of the northern kingdom are described in the Bible as all

irretrievably sinful; some of the kings of Judah are also said to have strayed

from the path of total devotion to God. In time, God sent outside invaders and

oppressors to punish the people of Israel for their sins. First the Arameans of

Syria harassed the kingdom of Israel. Then the mighty Assyrian empire brought

unprecedented devastation to the cities of the northern kingdom and the bitter

fate of destruction and exile in 720 BCE for a significant portion of the ten

tribes. The kingdom of Judah survived more than a century longer, but its people

could not avert the inevitable judgment of God. In 586 BCE, the rising, brutal

Babylonian empire decimated the land of Israel and put Jerusalem and its Temple

to the torch.

With that great tragedy, the biblical narrative dramatically departs in yet

another characteristic way from the normal pattern of ancient religious epics.

In many such stories, the defeat of a god by a rival army spelled the end of his

cult as well. But in the Bible, the power of the God of Israel was seen to be

even greater after the fall of Judah and the exile of the Israelites. Far

from being humbled by the devastation of his temple, the God of Israel was seen

to be a deity of unsurpassable power. He had, after all, manipulated the

Assyrians and the Babylonians to be his unwitting agents to punish the people of

Israel for their infidelity.

Henceforth, after the return of some of the exiles to Jerusalem and the

reconstruction of the Temple, Israel would no longer be a monarchy but a

religious community, guided by divine law and dedicated to the precise

fulfillment of the rituals prescribed in the community’s sacred texts. And it

would be the free choice of men and women to keep or violate that divinely

decreed order – rather than the behavior of its kings or the rise and fall of

great empires – that would determine the course of Israel’s subsequent history.

In this extraordinary focus on human responsibility lay the Bible’s great power.

Other ancient epics would fade over time. The impact of the Bible’s story on

western civilisation would only grow.

Saturday, 18 January 2014

Monday, 13 January 2014

Bible: The texts

Despite its name, the Bible is not a single, monolithic book. It is a collection of texts of multiple authors, places and times. Its diverse material ranges across history, law, prophecy, poetry and myth, and has been through centuries of editing, translating and reinterpreting. There is no agreement across religious communities about which texts belong in the Bible, and in what form. Different Bibles serve different groups, so the version you read depends on who you are.

As the Bible was originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic and ancient Greek, there is the additional complication that few can read the whole collection in the original. The vast majority of readers rely upon translations, which must by their nature interpret and re-imagine the text.

The three Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – all trace their history in some form to the Biblical figure of Abraham, but they have different attitudes to the Bible. For Christians, the Bible is divided into two: the Old and New Testaments, and Jesus was the messiah predicted in Old Testament prophecies. Jews believe the messiah is yet to come, and therefore do not accept as sacred the texts of the New Testament. Islam recognises certain Old Testament books as divinely inspired, but contends the texts are unreliable due to alteration by human hands, and that only the Quran, written to correct these problems, is authoritative.

What the Christians know as the Old Testament is known to Jews as the Tanakh. This name is an acronym, T-N-KH (the vowels were added later), referring to the three sections of the Hebrew Bible: the Torah, the Nevi’im and the Ketuvim. It is written in Hebrew apart from a few passages in Aramaic.

The first five books of the Bible are known to Jews by the first words of their respective texts, but to Christians as Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In Judaism, this is the Torah, best translated as ‘instruction’ or ‘teaching’, and forms the first section of the Tanakh. In Christianity, these five books are the Pentateuch (Greek, ‘five scrolls’) and form the first section of the Old Testament. A later tradition claims they were written by the prophet Moses, but that is not claimed by the texts themselves. They tell the story of the people of Israel, from the creation of the world through the flood and the exodus from Egypt to the desert wanderings and the covenant made with God at Sinai. The narrative ends with Moses and the Israelites on the brink of entering into Canaan, the promised land.

The next section of the Hebrew Bible is the Nevi’im, which means ‘prophets’. The first few books, Joshua through to 2 Kings (the Former Prophets), continue the historical narrative of Israel begun in the Torah. The Israelites cross into Canaan and conquer it, then eventually suffer defeat and exile at the hands of the Assyrians and the Babylonians. This provides a background to the next few books (the Latter Prophets), each named after the individual prophet who supposedly wrote the text. The most important are Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel, and there are also short texts by twelve minor prophets. The Torah and Former Prophets form most of the Bible’s ‘historical’ narrative, from the creation to the exile.

The final section is the Ketuvim, the Hebrew word for ‘writings’. This is a miscellany of various texts expressing the spiritual life of the Israelites, including the books of Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Ecclesiastes and Chronicles.

Non-Jewish readers who reached for a copy of the Bible while reading this will probably find that the books in it are not organised according to the outline above. The Christian version of the Bible has its own story, beginning with the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew Bible into ancient Greek produced in the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE to serve the Greek-speaking Jews who lived in the Hellenised Egypt of the post-Alexander period. This changed the order of the books and added some texts not in the Jewish canon, and became the basis for the Christian Old Testament. (Relying upon the Greek translation, Christians mostly didn’t revisit the original Hebrew text until the Reformation.) The very term ‘Old Testament’ expresses for Christians a relationship to the ‘New Testament’: the New does not merely follow the Old, it supersedes it.

Here I shall use ‘Old Testament’ as the general term, as it’s the most familiar in the culture I’m writing in, but will refer to the ‘Hebrew Bible’ when it’s necessary to differentiate the two.

In the 16th century CE the Reformation split Christianity into Catholic and Protestant traditions, and the contents of these traditions’ Bibles differ from each other. Some versions of the Old Testament also contain writings known as the Apocrypha, including the books of Esdras, Judith, Maccabees and others. These were considered less important by the Jews, but some Christian groups accepted them as canon, while other Christians rejected them. There is no need here to try and untangle all the different versions and groups. Suffice to say there are many canons serving many communities, and the Old Testament therefore takes a variety of forms. However, every version of the Bible contains, though not necessarily in the same order, the 24 books of the Tanakh outlined above.

A scholarly consensus has gradually emerged that the books of the Old Testament were written and redacted roughly between 1000-200 BCE – a period dominated by great ancient civilisations such as Babylon, Egypt and Assyria – though they may contain fragments of much older, oral communications. We can’t be certain who wrote them. We tend to think in bourgeois society’s terms of an author as a specific individual writing in a specific time, but in the ancient world texts were made differently. They are the product of long traditions of scholarship, put together over centuries by many hands, the writers acting as compilers and also interpreters of tradition.

No original Biblical manuscript has survived, as they would have been written on highly perishable papyrus or animal skin. The texts we have today were transmitted by centuries of hand-copying, translation and other fallible processes. Until the mid-twentieth century, the oldest surviving manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible were copies from the 9th and 10th centuries CE made by a group of Jewish scribes called the Masoretes. Ancient Hebrew did not include written vowels, so the Masoretes, concerned that the pronunciation might become lost, very carefully added vowels and punctuation to produce what is known as the Masoretic Text: the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible.

Page of the Aleppo Codex, written in the 10th century CE, considered by some the most authoritative Masoretic manuscript. The Codex was the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible until some pages were lost, whereupon that crown passed to the Leningrad Codex of 1008-10 CE.

The manuscript record was transformed between 1947-56 when hundreds of ancient manuscripts were found in a series of caves near the Dead Sea. One of the twentieth century’s greatest archaeological discoveries, the Dead Sea Scrolls were written in the 3rd to 1st centuries BCE by a strict religious community occupying the nearby site of Qumran, who hid them in about 70 CE while the Romans were conquering the region. Among them is the most ancient surviving Biblical manuscript: an almost complete copy of the book of Isaiah dating to at least 100 BCE. There were also fragments of almost all the other books of the Hebrew Bible, and various other texts.

The Biblical texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls were surprisingly consistent with the extant versions, a measure of the dedication of the scribes who went to great lengths to preserve them accurately, and of the remarkable stability of the texts over many centuries.

The New Testament is much shorter and compromises 27 books, written around 50-150 CE. Its diverse texts, traditionally ascribed to eight authors, range from accounts of the life of Jesus to letters to early Christian communities and the bizarre visions of Revelation. They are not accepted as scripture by Jews and therefore represent the split of the new Christian religion from Judaism.

They also represent a linguistic break. When they were being written, Hebrew was in decline as a spoken language even amongst Jews, who would commonly have spoken Aramaic. The heyday of ancient Greece, and above all the Hellenistic empire of Alexander, left a legacy of Greek-speaking culture from Egypt to Afghanistan. Therefore the most familiar version of the Hebrew Bible in Jesus’ time was the Septuagint. After the rise of the Roman Empire, Greek culture persisted as the language of scholarship, of literature and philosophy, and the New Testament writers naturally turned to it as the lingua franca of their world. They did not however write in the classical Greek of Plato and Aristotle, but in koine, a form of Greek understood by the common people.

The collection opens with the four Gospels (‘gospel’ means ‘good news’) of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which report the life, teachings and resurrection of Jesus. These are followed in the running order by the Acts of the Apostles or simply ‘Acts’, an account of the expansion of the early church after Jesus’ death. This was intended as a continuation of Luke’s gospel and was written by the same person. The main figures are Peter, leader of the twelve original followers or apostles, and the early church leader Paul of Tarsus, who is converted and finally makes a trip to Rome.

The next set of 21 books is the Epistles, a series of letters written by church leaders to a variety of Christian communities. The first fourteen are normally ascribed to Paul, whose target communities eventually lent their names to the texts: Romans, Corinthians, etc. After this come seven more letters, known as known as the Letters to all Christians, or ‘catholic’ letters, intended for Christians as a whole rather than particular communities. According to tradition they were written by James the brother of Jesus, Peter the apostle, John the Evangelist, and Jude, another brother of Jesus.

The final text is the Book of Revelation, a strange vision foretelling the end of the world and Jesus’s second coming.

Each book has its own writer and purpose – the New Testament, like the Old, is not a book so much as an anthology. The people writing the texts did not know they were writing a ‘new testament’ that would follow an ‘old testament’. Even the titles of most of the books were added later. The first books to be written, although they come after the gospels in the final running order, were the letters of Paul, the first being 1 Thessalonians from about 50 CE. These letters would have been copied by scribes and sent to different communities; the evidence for this comes from the texts themselves. For example, in early Greek manuscripts of the letter we now know as ‘Ephesians’, the recipient is left blank for the scribe to fill in as appropriate. Remarkably, Paul is the only named author in the Bible who can be confirmed as an actual historical figure.

The gospels were written about 20 or 30 years later. The gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were not written by the apostles of those names, but considerably later by people who were not eye witnesses of Jesus. Beside the four gospels that became canon, there were others, such as the gospels according to Thomas, Judas, and Mary. Why some texts were accepted into the Bible and others weren’t is a subject we’ll discuss later.

As with the Old Testament, no original manuscripts survive. The earliest copies of complete books date to about 200 CE, and the earliest complete New Testament is the 4th century Codex Sinaiticus.

As the Latin of the Roman empire replaced Greek as the dominant language, a Latin translation of both Testaments was created in about 400 CE by the scholar St Jerome. Known as the Vulgate, this translation became the standard edition of the Christian Bible for centuries. It was not until the Reformation that translation into other European languages began to be made: the most prestigious in the English-speaking world is the King James Bible of 1611, whose style, though now archaic, had an immense influence upon English literature. More recently there have been numerous further English editions, which aim for greater accuracy in a contemporary style.

A thousand years separate the writing of the first and last sentences of the Bible. In the ancient world the only way to preserve texts over generations was for scribes to make handwritten copies, first as scrolls and later as books. Acutely aware of the potential for human error, scribes often took immense care to make their copies accurate, but even so, different ancient editions of Biblical texts do not entirely agree. The Bible does not have a single ideology or style, nor did its compilers attempt to impose them. Each book reflects a different perspective on history, the world and how to live.

In the next few posts we will look at the Old Testament, beginning with how it was written and compiled.

As the Bible was originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic and ancient Greek, there is the additional complication that few can read the whole collection in the original. The vast majority of readers rely upon translations, which must by their nature interpret and re-imagine the text.

The three Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – all trace their history in some form to the Biblical figure of Abraham, but they have different attitudes to the Bible. For Christians, the Bible is divided into two: the Old and New Testaments, and Jesus was the messiah predicted in Old Testament prophecies. Jews believe the messiah is yet to come, and therefore do not accept as sacred the texts of the New Testament. Islam recognises certain Old Testament books as divinely inspired, but contends the texts are unreliable due to alteration by human hands, and that only the Quran, written to correct these problems, is authoritative.

The Old Testament

What the Christians know as the Old Testament is known to Jews as the Tanakh. This name is an acronym, T-N-KH (the vowels were added later), referring to the three sections of the Hebrew Bible: the Torah, the Nevi’im and the Ketuvim. It is written in Hebrew apart from a few passages in Aramaic.

The first five books of the Bible are known to Jews by the first words of their respective texts, but to Christians as Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In Judaism, this is the Torah, best translated as ‘instruction’ or ‘teaching’, and forms the first section of the Tanakh. In Christianity, these five books are the Pentateuch (Greek, ‘five scrolls’) and form the first section of the Old Testament. A later tradition claims they were written by the prophet Moses, but that is not claimed by the texts themselves. They tell the story of the people of Israel, from the creation of the world through the flood and the exodus from Egypt to the desert wanderings and the covenant made with God at Sinai. The narrative ends with Moses and the Israelites on the brink of entering into Canaan, the promised land.

The next section of the Hebrew Bible is the Nevi’im, which means ‘prophets’. The first few books, Joshua through to 2 Kings (the Former Prophets), continue the historical narrative of Israel begun in the Torah. The Israelites cross into Canaan and conquer it, then eventually suffer defeat and exile at the hands of the Assyrians and the Babylonians. This provides a background to the next few books (the Latter Prophets), each named after the individual prophet who supposedly wrote the text. The most important are Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel, and there are also short texts by twelve minor prophets. The Torah and Former Prophets form most of the Bible’s ‘historical’ narrative, from the creation to the exile.

The final section is the Ketuvim, the Hebrew word for ‘writings’. This is a miscellany of various texts expressing the spiritual life of the Israelites, including the books of Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Ecclesiastes and Chronicles.

Non-Jewish readers who reached for a copy of the Bible while reading this will probably find that the books in it are not organised according to the outline above. The Christian version of the Bible has its own story, beginning with the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew Bible into ancient Greek produced in the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE to serve the Greek-speaking Jews who lived in the Hellenised Egypt of the post-Alexander period. This changed the order of the books and added some texts not in the Jewish canon, and became the basis for the Christian Old Testament. (Relying upon the Greek translation, Christians mostly didn’t revisit the original Hebrew text until the Reformation.) The very term ‘Old Testament’ expresses for Christians a relationship to the ‘New Testament’: the New does not merely follow the Old, it supersedes it.

Here I shall use ‘Old Testament’ as the general term, as it’s the most familiar in the culture I’m writing in, but will refer to the ‘Hebrew Bible’ when it’s necessary to differentiate the two.

In the 16th century CE the Reformation split Christianity into Catholic and Protestant traditions, and the contents of these traditions’ Bibles differ from each other. Some versions of the Old Testament also contain writings known as the Apocrypha, including the books of Esdras, Judith, Maccabees and others. These were considered less important by the Jews, but some Christian groups accepted them as canon, while other Christians rejected them. There is no need here to try and untangle all the different versions and groups. Suffice to say there are many canons serving many communities, and the Old Testament therefore takes a variety of forms. However, every version of the Bible contains, though not necessarily in the same order, the 24 books of the Tanakh outlined above.

A scholarly consensus has gradually emerged that the books of the Old Testament were written and redacted roughly between 1000-200 BCE – a period dominated by great ancient civilisations such as Babylon, Egypt and Assyria – though they may contain fragments of much older, oral communications. We can’t be certain who wrote them. We tend to think in bourgeois society’s terms of an author as a specific individual writing in a specific time, but in the ancient world texts were made differently. They are the product of long traditions of scholarship, put together over centuries by many hands, the writers acting as compilers and also interpreters of tradition.

No original Biblical manuscript has survived, as they would have been written on highly perishable papyrus or animal skin. The texts we have today were transmitted by centuries of hand-copying, translation and other fallible processes. Until the mid-twentieth century, the oldest surviving manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible were copies from the 9th and 10th centuries CE made by a group of Jewish scribes called the Masoretes. Ancient Hebrew did not include written vowels, so the Masoretes, concerned that the pronunciation might become lost, very carefully added vowels and punctuation to produce what is known as the Masoretic Text: the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible.

Page of the Aleppo Codex, written in the 10th century CE, considered by some the most authoritative Masoretic manuscript. The Codex was the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible until some pages were lost, whereupon that crown passed to the Leningrad Codex of 1008-10 CE.

The manuscript record was transformed between 1947-56 when hundreds of ancient manuscripts were found in a series of caves near the Dead Sea. One of the twentieth century’s greatest archaeological discoveries, the Dead Sea Scrolls were written in the 3rd to 1st centuries BCE by a strict religious community occupying the nearby site of Qumran, who hid them in about 70 CE while the Romans were conquering the region. Among them is the most ancient surviving Biblical manuscript: an almost complete copy of the book of Isaiah dating to at least 100 BCE. There were also fragments of almost all the other books of the Hebrew Bible, and various other texts.

The Biblical texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls were surprisingly consistent with the extant versions, a measure of the dedication of the scribes who went to great lengths to preserve them accurately, and of the remarkable stability of the texts over many centuries.

The New Testament

The New Testament is much shorter and compromises 27 books, written around 50-150 CE. Its diverse texts, traditionally ascribed to eight authors, range from accounts of the life of Jesus to letters to early Christian communities and the bizarre visions of Revelation. They are not accepted as scripture by Jews and therefore represent the split of the new Christian religion from Judaism.

They also represent a linguistic break. When they were being written, Hebrew was in decline as a spoken language even amongst Jews, who would commonly have spoken Aramaic. The heyday of ancient Greece, and above all the Hellenistic empire of Alexander, left a legacy of Greek-speaking culture from Egypt to Afghanistan. Therefore the most familiar version of the Hebrew Bible in Jesus’ time was the Septuagint. After the rise of the Roman Empire, Greek culture persisted as the language of scholarship, of literature and philosophy, and the New Testament writers naturally turned to it as the lingua franca of their world. They did not however write in the classical Greek of Plato and Aristotle, but in koine, a form of Greek understood by the common people.

The collection opens with the four Gospels (‘gospel’ means ‘good news’) of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which report the life, teachings and resurrection of Jesus. These are followed in the running order by the Acts of the Apostles or simply ‘Acts’, an account of the expansion of the early church after Jesus’ death. This was intended as a continuation of Luke’s gospel and was written by the same person. The main figures are Peter, leader of the twelve original followers or apostles, and the early church leader Paul of Tarsus, who is converted and finally makes a trip to Rome.

The next set of 21 books is the Epistles, a series of letters written by church leaders to a variety of Christian communities. The first fourteen are normally ascribed to Paul, whose target communities eventually lent their names to the texts: Romans, Corinthians, etc. After this come seven more letters, known as known as the Letters to all Christians, or ‘catholic’ letters, intended for Christians as a whole rather than particular communities. According to tradition they were written by James the brother of Jesus, Peter the apostle, John the Evangelist, and Jude, another brother of Jesus.

The final text is the Book of Revelation, a strange vision foretelling the end of the world and Jesus’s second coming.

Each book has its own writer and purpose – the New Testament, like the Old, is not a book so much as an anthology. The people writing the texts did not know they were writing a ‘new testament’ that would follow an ‘old testament’. Even the titles of most of the books were added later. The first books to be written, although they come after the gospels in the final running order, were the letters of Paul, the first being 1 Thessalonians from about 50 CE. These letters would have been copied by scribes and sent to different communities; the evidence for this comes from the texts themselves. For example, in early Greek manuscripts of the letter we now know as ‘Ephesians’, the recipient is left blank for the scribe to fill in as appropriate. Remarkably, Paul is the only named author in the Bible who can be confirmed as an actual historical figure.

The gospels were written about 20 or 30 years later. The gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were not written by the apostles of those names, but considerably later by people who were not eye witnesses of Jesus. Beside the four gospels that became canon, there were others, such as the gospels according to Thomas, Judas, and Mary. Why some texts were accepted into the Bible and others weren’t is a subject we’ll discuss later.

As with the Old Testament, no original manuscripts survive. The earliest copies of complete books date to about 200 CE, and the earliest complete New Testament is the 4th century Codex Sinaiticus.

As the Latin of the Roman empire replaced Greek as the dominant language, a Latin translation of both Testaments was created in about 400 CE by the scholar St Jerome. Known as the Vulgate, this translation became the standard edition of the Christian Bible for centuries. It was not until the Reformation that translation into other European languages began to be made: the most prestigious in the English-speaking world is the King James Bible of 1611, whose style, though now archaic, had an immense influence upon English literature. More recently there have been numerous further English editions, which aim for greater accuracy in a contemporary style.

Conclusion

A thousand years separate the writing of the first and last sentences of the Bible. In the ancient world the only way to preserve texts over generations was for scribes to make handwritten copies, first as scrolls and later as books. Acutely aware of the potential for human error, scribes often took immense care to make their copies accurate, but even so, different ancient editions of Biblical texts do not entirely agree. The Bible does not have a single ideology or style, nor did its compilers attempt to impose them. Each book reflects a different perspective on history, the world and how to live.

In the next few posts we will look at the Old Testament, beginning with how it was written and compiled.

Wednesday, 1 January 2014

The Bible

The Bible (from the Greek for ‘book’) is a canon of sacred texts of Judaism and Christianity, a diverse anthology of Near Eastern literature with a geographical focus on the Mediterranean, Egypt and the Levant. It was the first book to be printed in the West, and according to Guinness World Records, it is the most widely-distributed piece of literature ever. Unfazed by its multitude of inconsistencies and historical errors, millions of people believe, with varying degrees of literalness, that it was inspired by a supernatural being who created the universe, and though rooted in the Bronze Age, the Bible texts continue to influence modern debates such as sexuality, women’s reproductive rights and human origins.

In the West, even atheists have a knowledge of the Bible which they do not usually have of writings from other religious traditions, such as the Bhagavad Gita or the Quran. Its memorable stories and characters – Adam and Eve, Noah and the Flood, the Nativity, David and Goliath and so on – are familiar across the world. Its influence upon art, both inside and outside Christian cultures and communities, is profound.

The Bible’s importance means it has been embellished and ideologically appropriated by all sorts of social groups and classes, from both the political left and the right. It has been used to justify war and oppression on one hand, and peace and liberation on the other. Though it is routinely believed to be the word of God, the Bible itself never makes that claim, and there are many Christian concepts – such as original sin, saints, the afterlife and the Devil – which appear either weakly or not at all. Complex doctrines such as the Holy Trinity were created by later scholars as they tried to clarify philosophical problems.

Biblical characters are fallible human beings struggling with themselves and society, not bland role models for bored children in Sunday school. The Bible is a book of selfishness, violence, sex, morality, even genocide, and it communicates in incredibly direct language.

Modern archaeology and other forms of study are helping us scrutinise the Bible from a scientific and historical standpoint. This approach is surprisingly recent, growing from the development of archaeology in the 19th century. Just two centuries ago, even such important ancient sites as Babylon and Nineveh were lost to history. Now, scholars are gradually piecing together the real history of the ancient Near East, and revealing the ancient Israelites as pioneers of monotheism, written history, and individual moral responsibility.

The temptation in the early days of Biblical research was to look at objects from the past as evidence of the verity of the Bible stories, and this tradition continues in the ‘Biblical Archaeology’ movement founded by William F. Albright. It is obvious that the Bible is full of material that cannot be literally true, calling into question its version of history. And if the Bible is unreliable as a source of historical information, its spiritual teachings may be also be unreliable. It is a lesson in the power of ideology and the human imagination that sometimes no abundance, or absence, of physical evidence is enough to dissuade people of their supernatural beliefs.

A text is only scripture for people who take it as scripture – for others, it is literature. For a materialist, the supernatural content is nonsense, but if the Bible isn’t the ‘Word’ of a supernatural being, this is not necessarily a reason not to read it. Tolstoy’s War and Peace is set in a real place during a real war, but as readers we accept that the truths it offers are literary, imaginative, social truths. We don’t dismiss the book as a pack of lies because historians have failed to find the physical remains of Andrei and Natasha. Similarly, the Bible does report historical events, occasionally accurately, but from a literary point of view the goal of the Old Testament is to illustrate how a deity defined the history of the Israelites, and the goal of the New Testament is to relate what happened during and after the life of Jesus. Without religion we can still appreciate the Bible’s social, literary and existential content.

To clarify some definitions: the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Israel were the Israelites. It is inaccurate to refer to ‘Jews’ until after the Persian occupation (7th century BCE), and there is a difference between the Israelites and the Israelis, who are citizens of the modern state of Israel from 1948 onwards. We shall use ‘Hebrew’ as a linguistic not an ethnic term, referring to the Biblical language.

When we refer to ‘scripture’ we mean a written text that a community believes is holy and authoritative. A ‘canon’ is a closed list telling which scripture is authoritative and which is not. It is much more fixed than when we refer, for example, to the ‘canon’ of English literature, which is open to challenge.

In the next few articles, we shall discuss topics such as how the Bible texts were compiled, the meaning of some of its key episodes, how the real history of the Israelites compares to the stories, and other fascinating things. Anyone interested in world culture past and present can enjoy exploring the background and content of this remarkable anthology.

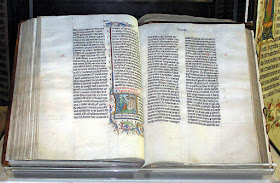

|

| Bible from Malmesbury Abbey, England, handwritten in Latin in 1407 CE. |

The Bible’s importance means it has been embellished and ideologically appropriated by all sorts of social groups and classes, from both the political left and the right. It has been used to justify war and oppression on one hand, and peace and liberation on the other. Though it is routinely believed to be the word of God, the Bible itself never makes that claim, and there are many Christian concepts – such as original sin, saints, the afterlife and the Devil – which appear either weakly or not at all. Complex doctrines such as the Holy Trinity were created by later scholars as they tried to clarify philosophical problems.

Biblical characters are fallible human beings struggling with themselves and society, not bland role models for bored children in Sunday school. The Bible is a book of selfishness, violence, sex, morality, even genocide, and it communicates in incredibly direct language.

Modern archaeology and other forms of study are helping us scrutinise the Bible from a scientific and historical standpoint. This approach is surprisingly recent, growing from the development of archaeology in the 19th century. Just two centuries ago, even such important ancient sites as Babylon and Nineveh were lost to history. Now, scholars are gradually piecing together the real history of the ancient Near East, and revealing the ancient Israelites as pioneers of monotheism, written history, and individual moral responsibility.

The temptation in the early days of Biblical research was to look at objects from the past as evidence of the verity of the Bible stories, and this tradition continues in the ‘Biblical Archaeology’ movement founded by William F. Albright. It is obvious that the Bible is full of material that cannot be literally true, calling into question its version of history. And if the Bible is unreliable as a source of historical information, its spiritual teachings may be also be unreliable. It is a lesson in the power of ideology and the human imagination that sometimes no abundance, or absence, of physical evidence is enough to dissuade people of their supernatural beliefs.

A text is only scripture for people who take it as scripture – for others, it is literature. For a materialist, the supernatural content is nonsense, but if the Bible isn’t the ‘Word’ of a supernatural being, this is not necessarily a reason not to read it. Tolstoy’s War and Peace is set in a real place during a real war, but as readers we accept that the truths it offers are literary, imaginative, social truths. We don’t dismiss the book as a pack of lies because historians have failed to find the physical remains of Andrei and Natasha. Similarly, the Bible does report historical events, occasionally accurately, but from a literary point of view the goal of the Old Testament is to illustrate how a deity defined the history of the Israelites, and the goal of the New Testament is to relate what happened during and after the life of Jesus. Without religion we can still appreciate the Bible’s social, literary and existential content.

To clarify some definitions: the inhabitants of the ancient kingdom of Israel were the Israelites. It is inaccurate to refer to ‘Jews’ until after the Persian occupation (7th century BCE), and there is a difference between the Israelites and the Israelis, who are citizens of the modern state of Israel from 1948 onwards. We shall use ‘Hebrew’ as a linguistic not an ethnic term, referring to the Biblical language.

When we refer to ‘scripture’ we mean a written text that a community believes is holy and authoritative. A ‘canon’ is a closed list telling which scripture is authoritative and which is not. It is much more fixed than when we refer, for example, to the ‘canon’ of English literature, which is open to challenge.

In the next few articles, we shall discuss topics such as how the Bible texts were compiled, the meaning of some of its key episodes, how the real history of the Israelites compares to the stories, and other fascinating things. Anyone interested in world culture past and present can enjoy exploring the background and content of this remarkable anthology.